Su nombre completo era William Matthew Flinders Petrie. El padre de Petrie era ingeniero civil y su madre, Anne era una enamorada de la ciencia, ambos siempre animaron a Petrie para que siguiera siempre los estudios que había elegido.

Al principio Petrie estudia trigonometría y geometría. Se interesó también en las medidas de edificaciones, iglesias y ruinas megalíticas, como Stonehenge, a los trece lee una obra de Piazzi Smyth titulada “Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramids” y comienza a interesarse en las pirámides de Egipto y desea poder mediarla él mismo. (Charles Piazzi Smyth buscaba las dimensiones de la gran pirámide)

Comienza a realizar trabajar como topógrafo en el sur de Inglaterra y durante ese tiempo tambien sigue estudiando Stonehenge. Petrie determinó la unidad de medido usada en la construcción de Stonehenge en eal año 1880, cuando contaba 24 años de edad publica su primer libro, un estudio interesantísimo sobre Stonehenge titulado “Stonehenge: Plans, descripction and theories".

Después de esa publicación, Petrie comienza a interesarse por Egipto, de tal manera, que durante el resto de su vida se va a dedicar a explorar, examinar y estudiar Egipto y oriente medio.

Petrie en el Museo. año 1921

Desde 1880 a 1883, Petrie realiza excavaciones y estudia todo lo referente a la gran pirámide de Giza, Era un hombre muy meticuloso y realizaba las excavaciones de forma que crea innovaciones en los métodos científicos de excavación.

En el año 1884, descubrió los fragmentos de la estatua de Ramses II, en sus excavaciones en el templo de Tanis.

Posteriormente dedica los siguientes dos años en realizar excavaciones en el delta del Niloo , en sitios como Naukratis y Daphnae. Consiguió clasificar la cerámica, comparando fragmentos también con la datación relativa a partir de los estilos de alfarería hallados en diferentes lugares.

Los siguientes cuatro años los dedica a explorar y excavar más de treinta lugares en el medio oeste. Descubre bastantes cosas interesantes, como la famosa estela de Mernepath en Tebas.

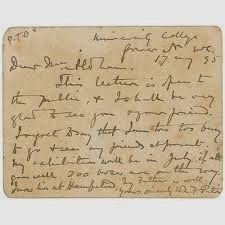

Flinders Petrie fue nombrado profesor de egiptología en la University College de Londres ,(Edwards Profesor of Egyptian Archeology and Philology) el año 1892 (catedra fundada por Amelia Edwards) . En el año 1913 vendió al University College su colección personal de antigüedades egipcias.

Petrie fue también escritor, autor de más de cien libros y unos 900 artículos y revistas.

En 1927, Petrie vuelve a Palestina y allí excavó varios lugares fronterizos entre Egipto y Canaan como por ejemplo Tell el Hesi.

Permanece allí hasta que muere a la edad de 85 años, en Jerusalén el 28 de julio de 1942.

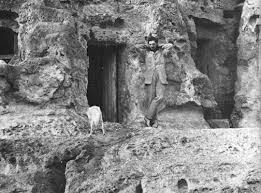

Petrie 1896

Flinders Petrie y su esposa en Menfis, en 1910

_Flinders_Petrie_by_George_Frederic_Watts.jpg)