miércoles, 28 de octubre de 2015

Necklaces of faience beads and pendants

Necklaces of faience beads and pendants

Canaanite, about 1500-1200 BC

From Lachish (modern Tell ed-Duweir), Israel

Egyptian fashions in the southern Levant

These fine necklaces from the Fosse Temple at Lachish illustrates the strongly Egyptianizing style of Cannanite art of the Late Bronze Age. During this period the southern Levant was under Egyptian domination. Lachish is referred to in the Amarna letters - a group of clay tablets written in Babylonian cuneiform found at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt and preserving diplomatic correspondence to Egyptian pharaohs from vassal kings. The ruler of Lachish was Shipti-ba’al, a vassal king, subject to the firm control of Egypt, and enjoying the wealth and security that such political domination provided.

The so-called Fosse Temple was a small sanctuary first built around 1550 BC in the disused moat (fosse) that had formed part of the fortifications of Lachish in the early second millennium. A sudden destruction in about 1200 BC left remarkable contents in position in the building. These included many vessels containing the bones of animal offerings, and also rich finds of glass, faience and alabaster, imported pottery, ivories and jewellery in many materials, including gold and silver.

British Museum

britishmuseum.org

Canaanite, about 1500-1200 BC

From Lachish (modern Tell ed-Duweir), Israel

Egyptian fashions in the southern Levant

These fine necklaces from the Fosse Temple at Lachish illustrates the strongly Egyptianizing style of Cannanite art of the Late Bronze Age. During this period the southern Levant was under Egyptian domination. Lachish is referred to in the Amarna letters - a group of clay tablets written in Babylonian cuneiform found at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt and preserving diplomatic correspondence to Egyptian pharaohs from vassal kings. The ruler of Lachish was Shipti-ba’al, a vassal king, subject to the firm control of Egypt, and enjoying the wealth and security that such political domination provided.

The so-called Fosse Temple was a small sanctuary first built around 1550 BC in the disused moat (fosse) that had formed part of the fortifications of Lachish in the early second millennium. A sudden destruction in about 1200 BC left remarkable contents in position in the building. These included many vessels containing the bones of animal offerings, and also rich finds of glass, faience and alabaster, imported pottery, ivories and jewellery in many materials, including gold and silver.

British Museum

britishmuseum.org

Letter from Tushrata to Amenhotep III

Letter from Tushrata to Amenhotep III

Mitannian, about 1370-1350 BC

From Tell el-Amarna, Egypt

...

Mitannian, about 1370-1350 BC

From Tell el-Amarna, Egypt

...

Diplomatic links between Mesopotamia and Egypt

This clay tablet is part of a collection of 382 cuneiform documents discovered in 1887 in Egypt, at the site of Tell el-Amarna. They are mainly letters spanning a fifteen- to thirty-year period. The first dates to around year 30 of the reign of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BC), and the last to no later than the first year of the reign of Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BC). The majority date to the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) (1352-1336 BC), the heretic pharaoh who founded a new capital at Tell el-Amarna.

This letter is written in Akkadian, the diplomatic language of Mesopotamia at the time. It is addressed to Amenhotep III from Tushratta, king of Mitanni (centred in modern Syria). Tushratta calls the pharaoh his 'brother', with the suggestion that they are of equal rank. The letter starts with greetings to various members of the royal house including Tushratta's daughter Tadu-Heba, who had become one of Amenhotep's many brides. Diplomatic marriages were the standard way in which countries formed alliances with Egypt.

Tushratta goes on to inform Amenhotep that, with the consent of the goddess Ishtar, he has sent a statue of her to Egypt. He hopes that the goddess will be held in great honour in Egypt and that the statue may be sent back safely to Mitanni.

Three lines of Egyptian, written in black ink, have been added, presumably when the letter arrived in Egypt. The addition includes the date 'Year 36' of the king.

W.L. Moran, The Amarna letters (John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1992)

http://www.britishmuseum.org/

This clay tablet is part of a collection of 382 cuneiform documents discovered in 1887 in Egypt, at the site of Tell el-Amarna. They are mainly letters spanning a fifteen- to thirty-year period. The first dates to around year 30 of the reign of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BC), and the last to no later than the first year of the reign of Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BC). The majority date to the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) (1352-1336 BC), the heretic pharaoh who founded a new capital at Tell el-Amarna.

This letter is written in Akkadian, the diplomatic language of Mesopotamia at the time. It is addressed to Amenhotep III from Tushratta, king of Mitanni (centred in modern Syria). Tushratta calls the pharaoh his 'brother', with the suggestion that they are of equal rank. The letter starts with greetings to various members of the royal house including Tushratta's daughter Tadu-Heba, who had become one of Amenhotep's many brides. Diplomatic marriages were the standard way in which countries formed alliances with Egypt.

Tushratta goes on to inform Amenhotep that, with the consent of the goddess Ishtar, he has sent a statue of her to Egypt. He hopes that the goddess will be held in great honour in Egypt and that the statue may be sent back safely to Mitanni.

Three lines of Egyptian, written in black ink, have been added, presumably when the letter arrived in Egypt. The addition includes the date 'Year 36' of the king.

W.L. Moran, The Amarna letters (John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1992)

http://www.britishmuseum.org/

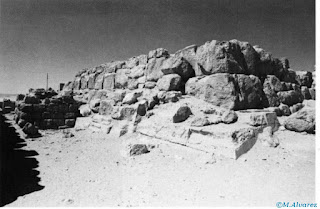

Mastabet el-Fara'un

Isometric views of the mastaba of Shepseskaf taken from a 3d model

Saqqara

The structure is located close to the pyramid of Pepi II

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum . mural drawing

An Egyptian burial chamber mural, from the tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum dating to around 2400 BC, showing wrestlers in action

plaque

Ivory plaque with the name of Nebty Djeserty (ie. Sekhemkhet) and a list of linen fabrics. The inscription in the lower section of the plaque describes several different types of clothes such as bed sheets, shirts, nightgowns, vestments and even underwear. The central section names them or describes their size and colour. The upper section bears the reading "the king lives!", at the right several Horus falcons are depicted, the line on which they sit ends in an ostrich feather (a symbol of light and harmony) Provenance: Saqqara. Step Pyramid of Horus Sekhemkhet. Found in 1955, by Z. Goneim, the floor of the main hall of the pyramid. Cairo, Egyptian Museum, JE 92679 Goneim, Z. 1957. "Horus Sekhem-Khet". Pl LXV b.

barque with two human figures

Burial object, barque with two human figures, Gebelein, Upper Egypt. Probably Naqada II, 3400-3200 BC. Clay-covered reed

jueves, 22 de octubre de 2015

Pottery figure of a woman

Pottery figure of a woman with red painted features (lips, ears, necklace, armlet and feet) and black features (hair, necklace and armlet). Found at Abu Sir and is from the late New Kingdom

Petrie Museum

http://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk

domingo, 11 de octubre de 2015

GIZA

Street G 7100, looking south, toward Khafkhufu chapel G

7140, with socket of wife’s chapel, G 7130, in foreground

7140, with socket of wife’s chapel, G 7130, in foreground

Embrasure, façade, south side, lower part covering by later vault

Khakhufu chapel, G 7140

Khakhufu chapel, G 7140

The two tombs of Inerkhau , (TT359 and TT299).

The following scene represents Inerkhau, standing, his arms raised in a sign of worship. An immense snake, named Sata (= literally "Son of the land"), faces him (view 13bis).

These reptiles play an ambiguous role in Egyptian mythology. Sometimes, they embody hostile, dangerous and unverifiable strengths, sly adversaries of the created world; sometimes they are the embryonic shapes of divine beings, or even the greatest gods imaginable before the spreading of the creation of the universe. Sata belongs to this last category, and §87 of the Book of the Dead (to which this image could serve as a vignette but which doesn't correspond to the text reproduced here) has clearly assimilated the nocturnal sun, which it then regenerates in the beyond before being born again at dawn. This is why Inerkhau addresses a hymn to it and venerates such a great god.

The two tombs of Inerkhau , (TT359 and TT299).

, (TT359 and TT299).

osisisnet.net

These reptiles play an ambiguous role in Egyptian mythology. Sometimes, they embody hostile, dangerous and unverifiable strengths, sly adversaries of the created world; sometimes they are the embryonic shapes of divine beings, or even the greatest gods imaginable before the spreading of the creation of the universe. Sata belongs to this last category, and §87 of the Book of the Dead (to which this image could serve as a vignette but which doesn't correspond to the text reproduced here) has clearly assimilated the nocturnal sun, which it then regenerates in the beyond before being born again at dawn. This is why Inerkhau addresses a hymn to it and venerates such a great god.

The two tombs of Inerkhau

osisisnet.net

lunes, 5 de octubre de 2015

Amulet- Pendant, Nephthys

Amulet- Pendant, Nephthys

A cast silver amulet representing the goddess Nephthys, the sister of Isis, standing. She wears a small crown surmounted by the hieroglyph for her name. There is a loop behind the crown and the legs are broken off.

http://art.thewalters.org/

A cast silver amulet representing the goddess Nephthys, the sister of Isis, standing. She wears a small crown surmounted by the hieroglyph for her name. There is a loop behind the crown and the legs are broken off.

http://art.thewalters.org/

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)